REBEL

MAŁGORZATA SZAEFER

Miroslav Tichý – a Tarzan retired, a samurai, an atomist, an observer, an adherent of chaos, a voyeur, an anarchist. Roman Buxbaum’s film “Miroslav Tichý. Tarzan Retired” is an abundant source of the outsider’s uncompromising statements. “I don’t exist at all. I’m a tool. A tool of perception perhaps.”1 These words perfectly convey the artist’s outsider nature in which consciousness transcends the border of the unconscious. It bears relation to inscrutable time, life, mathematics, chaos. “Can you tell me what life is?” – he asks. “Define it!” And he concludes: “Every knowledge is limited. Now apply this to the numbers. What is the highest number and what is the lowest? We recognise only that which we can, and want to, recognise.”

A mathematical investigation into the insignificance of the universe. An attempt to recognise what is possible, tangible, but illusory at the same time, because the world, as Tichý used to say, is an illusion, a dream, a fantasy. Miroslav Tichý’s photographs possess the power of metaphysical questions. The aspect of free time, boredom, observation is intertwined in his case with mathematical precision and metaphysical mystery. “I see forms and I transfer them into mathematics. I must fit all of this together, not just the optical vision. From the externals to the inwards, I explore every atom. This makes me an atomist.”

For Tichý, “boredom” was the main tool of discovering the world. His photographs present him as someone who has never done anything beyond “letting time pass by.” The total, absolute oeuvre of the photographer also tells the story of a rebel, a renegade, an outsider who unintentionally found his own place in the world owing to the medium of photography. He perfectly realised the rules of the world and art: “If you want to be famous, you must do something more badly than anybody else in the entire world. Something beautiful and perfect is of no interest to anyone.” After all, banality is art’s worst enemy. Tichý became an eulogist of boredom – “the existential equivalent of cliché,” as Joseph Brodsky called it.2 While documenting reality, the Tarzan of Kyjov gave himself over to what people call loitering, wasting time, utter idleness. He gave himself over to boredom. His presence was a state of seeming inaction, slowness of thinking, unconstrained reflection, contemplation. This is the nature of his photographs – they are images that speak of beauty, transience of the moment, sensuality of the world.

Tichý admitted: “I go to town and must do something, rather than just take a walk. So I was simply pressing the release. /…/ That happens without any effort on my part.” Part of his vision was indicated by fate, by the Earth, whereas another part followed time that slowed down and the eye of the observer, who himself becomes a tool used by time. Tichý heavily emphasised that everything “was determined by time, as the day passed by. Everything is decided by the Earth, which is turning.” We are said to surpass time in terms of our sensitivity. Sensitivity is a mark of Tichý’s photographs.

Tichý admitted: “I go to town and must do something, rather than just take a walk. So I was simply pressing the release. /…/ That happens without any effort on my part.” Part of his vision was indicated by fate, by the Earth, whereas another part followed time that slowed down and the eye of the observer, who himself becomes a tool used by time. Tichý heavily emphasised that everything “was determined by time, as the day passed by. Everything is decided by the Earth, which is turning.” We are said to surpass time in terms of our sensitivity. Sensitivity is a mark of Tichý’s photographs.

Were boredom and time indeed Tichý’s tools? Or maybe it was Tichý who became a tool for time and boredom to use? It is difficult to pass an unequivocal judgement, especially as far as the outsider figure is concerned. However, Brodsky also wrote that “boredom is a complex phenomenon and by and large a product of repetition.”3 It allows us to discover something that is seemingly inconspicuous, banal, casual – the passage of ordinary events. “For boredom speaks the language of time, and it is to teach you the most valuable lesson in your life… the lesson of your utter insignificance.”4 According to Brodsky, boredom is an invasion of time that sets life in an appropriate perspective. Boredom allows us to understand insignificance, to sense finitude.

Contrary to appearances, understanding insignificance and sensing finitude determine the field of freedom and the power of opposition to what constrains us. Tichý built his autonomous world that flourished after his time spent in prison and mental asylums. The consciousness of his teleology and faithfulness to his own rules allowed him to last throughout time and enjoy freedom. His acute sense of observation activated his awareness of choice. Tichý’s photographs were underpinned by the negation of the totalitarian regime in Czechoslovakia, a country kept under a yoke. They are images of discord to the five-year plan, to the ban on nude studies at art schools, to military service, to doing time. They are images by a rebel who created everything anew, once again, in order not to use anything that was considered the norm. Such photographs could be created only by a free and independent man, unsubordinated to anything and anybody.

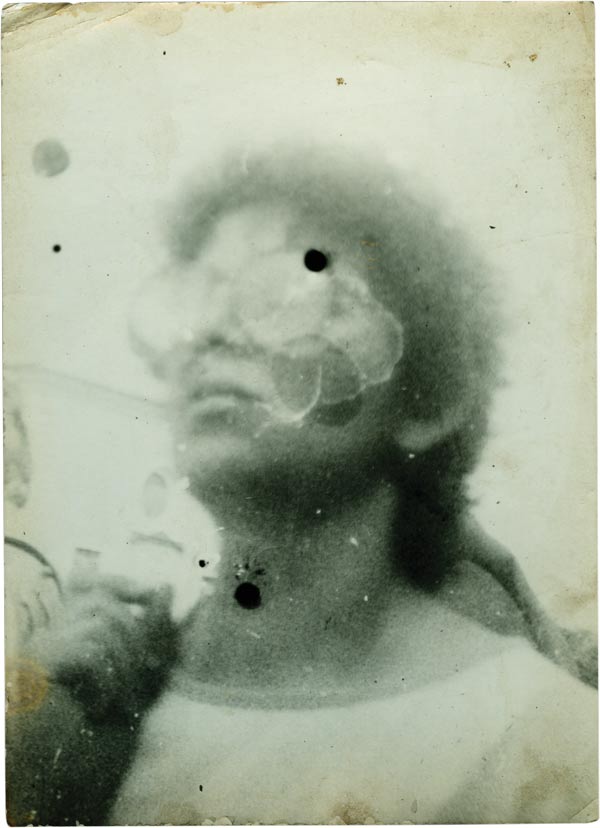

Writing about Tichý, Harald Szeemann remarked: “Intensity always finds its medium.”5 This is an extremely pertinent thought, particularly with regard to Tichý, who – being a fragment of the world – also reflects the world with all its imperfections, errors, contingency and necessity. The aesthetics of error became his trademark. Tichý built photographic cameras made of trash and found objects that were redundant, worn-out and no longer useful. He changed their meaning and gave them the status of indispensable and necessary fragments of a photographic camera mechanism. He built telescopic lenses using old glasses or plexiglass cut with a knife and then polished with sandpaper and toothpaste mixed with cigarette ash. His telescopic lenses were made of paper tubes to which he attached lenses using asphalt and painted them black. He used reels left after thread or elastic string to create a mechanism that triggered the shutter. The aesthetics of error also determined the technological aspects of developing prints. Precision and laboratory-like sterility were absolutely foreign notions to Tichý. There are several characteristics that determine the poetics of his prints. They would not exist without chaos and more or less conscious errors: “The flaws are part of it. That’s the poetry, the pictorial quality,” as Tichý explained. The margins of the photographs are bitten by mice, they bear traces of fingertips and stains of precipitated bromine. They are covered with layers of dust. All of this quite literally highlights the insignificance of the world, its transience. Tichý pursued a completely independent activity according to his own rules and against the status quo. The photographs provide a kind of renewable record determined by his own anarchistic gesture of discord to the existing reality. “To achieve that, you need first of all a bad camera…”

Tichý used to leave home around six in the morning and roamed the town with his photographic camera. His negatives and prints provide the only testimony to his everyday life. They show his favourite places on the repeated route of the outsider’s stroll. He began photographing at the bus station, then he crossed the main square in Kyjov, passed the church, the milk bar, the pharmacy. In a nearby shop he bought a few reels of photographic film. Then he approached the park with an adjacent lido – the final destination of the attentive observer. When the ban was imposed on nude studies at art schools in 1948, the lido in Kyjov became for Tichý a site of observation and studies of the female nude. His black and white photographs emanate the warmth of the female body, erotic fascination, but also mathematical pattern of perfection. They convey vivacity, youth, joy, sensuality. Fragments of film frames overexposed to sunlight, idleness, boredom and slowly passing time – all these aspects generate the aura of a never-ending hot summer. The foreground of many photographs features a fence that separates Tichý from women who are swimming in the pool and sunbathing. The fence marks a clear border and stands for the lack of access, which Nick Cave referred to in the lyrics to his song “The Collector”: “A bathing beauty in a cage.” All of this seems to highlight the vital fact that for Tichý the world is a woman… it is everything… “I am an observer of everything!”

He took his photographs quickly, from a distance. He said: “Photography is perception – the eyes – that which you see. And it happens so fast that you may not see anything at all.” He carried the camera under his sweater and “captured” the images with swift movement akin to a photojournalist, scanning reality. Tichý had his own five-year plan. “I have set myself a norm: so and so many photos per day, so and so many photos in five years.” Accordingly, he arranged chaos in a certain order by using three photographic film reels a day. More than one hundred photographs each day. He derived his power from ordering the chaos… “I’m a prophet of decay and a pioneer of chaos, because only from chaos does something new emerge.” Tichý inserted his photographs between book pages, he collected them in a large metal box which he kept under his bed in order to always have them within his reach. He trod on his prints, slept on them, put them under the legs of his table. Paradoxically enough, the signs of this abnegation became the power of Tichý’s photographs. Whenever he liked a particular photo, he cropped it and cut a cardboard frame for it. He sometimes drew details on photographs, using a pencil to mark the outline of a leg or an eye of a photographed person.

Those fractions of seconds captured in his photographs make up an astonishing record of time, which today is already dispersed and sometimes even irrevocably lost. What is left is a testimony to the existence of little, seemingly finite trivialities in which nothing seems to happen, and yet they pose the question about the sense of it all. “What’s the highest number? What’s the lowest number? There is no such thing. That’s infinity.”

1 All quoted statements by Miroslav Tichý originate from the film “Miroslav

Tichý. Tarzan Retired” directed by Roman Buxbaum and from Buxbaum’s essay “Miroslav Tichý. Tarzan Retired”, in “Miroslav Tichý” (New York: International Center of Photography, 2010), p. 307–320.

2 J. Brodsky, “In Praise of Boredom,” in “On Grief and Reason. Essays” (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), p. 105.

3 J. Brodsky, “In Praise of Boredom,” p. 104.

4 J. Brodsky, “In Praise of Boredom,” p. 109.

5 H. Szeemann, “Miroslav Tichý,” in “Miroslav Tichý. L’homme à la Mauvaise Camera” (Bruxelles: Galerie Pascal Polar, 2012, p. 19).